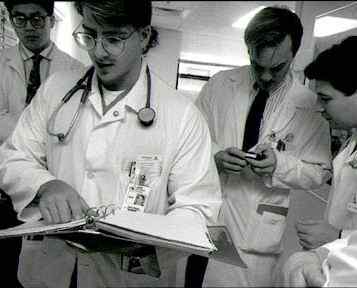

The “July Effect”: New Residents and New Obstacles

If you’ve been feeling under the weather as of late, you may soon be

able to breathe a big sigh of relief, according to Nurse Theresa Brown.

Citing to two recently published studies in her July 15

New York Times column, Brown, who is an oncology nurse, discusses what has been referred

to as the “July Effect” that takes place during the summer months

in hospitals when freshly-graduated medical students first gain experience

with actual patient care, primarily in the month of July.

“[July is] the month when medical residents, newly graduated from

medical school, start learning how to be doctors” by taking care

of patients, according to Brown.

And what does this learning process entail?

“Making mistakes.”

Though unable to specifically say whether this “July Effect”

has a measurable impact on fatal hospital errors, Brown maintains that

the changes in both adequacy and quality of care delivery in hospitals

during this time are “undeniably real.” Acknowledging the existing

disagreement in medical literature as to validity of this effect, Brown

points to a 2011 article led by Dr. John Q. Young and appearing in the

Annals of Internal Medicine in which Dr. Young makes an interesting analogy to explain this proposed

discrepancy in care. This migration of new residents to hospitals would

be akin to replacing veteran football players with rookies during “a

high-stakes game, and in the middle of that final drive,” according

to Young, due to their having little knowledge of how real medical problems

play out in real-life situations.

While Brown herself is unaware of any specific or measureable increase

in life-threatening or other medical error, she has certainly seen firsthand

the kind of detriment that patients can suffer due to the lack of “in-game”

experience endemic to new residents. In describing this disconnect between

resident and patient in both the adequacy and quality of care that is

administered, Brown recounts an example of when she witnessed a patient’s

literal suffering as a result of a new resident’s simple lack of experience.

The patient, suffering from cancer and actively dying, was entering into

the final stages of his fight for life and had begun to suffer the severe

pains that are often associated with dying cancer patients. After being

given oxygen to ease his breathing, Nurse Brown sought the permission

of the newly assigned resident to increase the patient’s dosage of

pain medication in order to help ease the pains of dying. The resident,

a July arrival and an M.D. on the books, refused to increase the dosage.

Though the doctor was likely following what he was taught to do in the

event of administering high doses of potentially lethal pain medication

to patients, Nurse Brown simply could not allow the patient to continue

to die in such agonizing pain.

With the patient twisting and crying out in pain, and the resident remaining

steadfast in his refusal to administer enough medication to sufficiently

quell the patient’s pain, Nurse Brown jumped to the top of the chain

of command, ultimately receiving the blessing of the on-call palliative

care physician. Hours later when Nurse Brown finally saw the resident

again, she tried to apologize for jumping him in the chain of command.

No sooner had she started her apology, however, than she was interrupted

by an equally apologetic resident, who told her succinctly that “[she]

did the right thing for the patient.”

Though Brown acknowledges the rarity of such exchanges given that nurses

are not typically consulted by doctors about decisions on how to administer

care, this exchange (as well as the “July Effect” in general)

brings some realities of hospital care into sharp focus. With care becoming

more and more specialized, nurses with years of experience may often times

know what is best for patient care than some of the greenest of physicians.

This is a fact that must be recognized and acknowledged, as all of those

involved in the care of hospital patients must own up to their shared

responsibility in successfully providing this care. Admitting that new

residents can and often do receive legitimate help from their nurses is

an important step, as this collaboration (as opposed to subordination)

between doctors and nurses can only serve to help provide more accurate

and personalized care to hospitalized patients.

Source: Brown, Theresa. “Don’t Get Sick in July.”

New York Times, 15 July, 2012.